Adapted from the original email-letters from Paul Ovaitt - Original date April 29, 2022

(Turn on your sound and press the play button to the right for the full experience!)

Gentle readers, how would you…write a story about death and the dismal trade? I guess most of you would never even embark on such a task. But in my last story, The Village Blacksmith, I promised to go there, and why not? Some people already jokingly, I hope, refer to me as the Grim Reaper and even a buzzard, because I often interview people of…advanced age. Oh well…someone’s got to do it…just like someone’s got to bury the dead or scatter their ashes.

Of course, if you were a Trappist monk, you’d be digging your own grave, so to speak, every day. I have often heard these monks do that, but after a vigorous internet search, all I found was this old article in The San Francisco Call, dated November 27, 1898. It said, “When a Trappist monk grows old and feels the end approaching, he finds time from his other labors to begin the digging of his own grave, an occupation that must indeed be conducive to solemn and religious thought.” I also found this curious cartoon: see attachment labeled Trappist monk.

Now, while I’m on this self-sufficiency kick, consider this: The monks of New Melleray Abbey in rural Peosta, Iowa, produce caskets for both themselves and sale to the public, according to a Wikipedia post.

Okay, enough grim humor…time for an interview. Let’s start with Jim Pitman, and eventually Eric Pitman, owners of 5 funeral homes in our general area. (Anything in parentheses is my writing.)

Jim Pitman: I was born in 1932 at Deaconess Hospital in STL, but my parents (Tarlton and Annetta Pitman) lived in Wentzville.

Paul: I spoke once to Penny Pitman (a board member of the Boone Duden Historical Society) and I learned that she was a descendant of Daniel Boone.

JP: And so am I.

P: Your ancestors came to Missouri at about the same time as the Boones (around 1800). And I’m guessing you had ancestors in the Revolutionary War.

JP: Yes, and we came through Kentucky.

P: Just like Boone. Tell me about your schooling.

JP: I went to grade school in Wentzville, eight years. I went into high school at Missouri Military Academy in Mexico, MO. I graduated in 1950, then went to Westminster College in Fulton, MO for two years. After that I went to St. Louis College of Mortuary Science for another two years.

P: Did you always have a sense you would go into the mortuary business because your dad was in it?

JP: Yes, my dad (Tarlton) died when I was in high school, my senior year at the Military Academy. And I knew, with my mom taking care of the funeral business, she needed help, and I decided at that time to go into the funeral business.

P: Let’s look at your youth some more. Do you have interesting recollections about growing up in the Wentzville area?

JP: Oh yes. When I grew up, there was hardly anybody here, and I remember families coming in on a wagon into town and doing their shopping. They would pull in… back of our…we had the Mercantile store at that time…. They’d park the wagons and horses back there in the shade, and what was always enjoyable to me…is that the women would come into our store and do the shopping…and the men would go across the street to the tavern and have drinks together.

P: Those were the good old days.

JP: That’s right.

P: From what I’ve read, your dad started his funeral business in 1922, 10 years before you were born.

JP: Dad was already in the funeral business at that time, and when there was a death, they had to go by horseback to the homes and do the embalming in the home. Then he finally opened a place…it was just down the street from the Mercantile. But before he owned the Mercantile, he was in the egg and hide business. And the people from the Mercantile asked him if he would come and manage the Mercantile, and that’s when we went there. And I lived above the Mercantile until 1941, and that was the year the war started.

P: Before that, were you living on a farm?

JP: Right. But about the egg and hide business: the farmers would bring their eggs and their cow hides in (to Wentzville) and then he’d ship them into STL. So that’s where he first started, but he was born in Howell.

P: But he left Howell well before the TNT days. Did he have any strong feelings on that topic? (From 1941 to 1945, the Weldon Spring Ordnance Works produced explosives for the U.S. Armed Services as part of the World War II defense effort. The US Government evacuated and destroyed Howell, Toonerville, and Hamburg for this war effort.)

JP: Oh yes, they were not very happy. There was a lot of fighting, not physical as much as talking…about what the government was doing…taking away the farms.

P: I think you told me Muschany, who owned the funeral home in Augusta before you, was from the TNT area.

JP: Yes. Muschany had a funeral home in Howell when the TNT broke up everybody (1940). He moved into New Melle and then he also opened a place in Wentzville also. We were actually competitors for a while. (Eventually) I bought Muschany out and that’s when I started in Augusta.

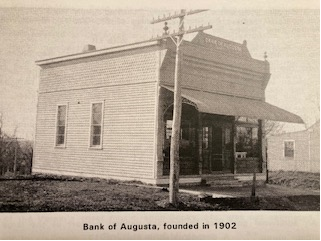

Gentle readers, I couldn’t determine just when Mr. Muschany started the funeral home in Augusta, or if there was one there that Muschany bought. Most of my readers would know that the Bank of Augusta was there first. The bank was founded in 1902, but unfortunately failed in December 1931 during the Great Depression. My best guess is that Muschany started a funeral home in the bank building in the early 1940s. See the attached photo of the bank and a closeup of the steel door of the bank’s vault. In a follow-up story, I’ll share more photos of the vault.

If anyone wishes to learn more about bank failures in our area, here’s a link to a story by local historian, Bob Brail. http://justawalkdowntheroad.blogspot.com/2016/10/thebank-failures-of-1931-bybob-brail.html

P: On your funeral home in Augusta, the sign reads Pitman-Thilking.

JP: Yes, we always carried Olie with us. He was well known in the area, and we kept his name with it. He was one great individual and when I bought the Muschany funeral home, Olie worked for Muschany. He ran the home in Augusta. He also ran a delivery business. He delivered oil and gas to the farmers around Augusta and Defiance…Femme Osage…wherever. And he remained an employee with us. He was one great individual.

P: Did they embalm bodies in the building when Olie Thilking ran the business?

JP: Yes, they had an embalming room back there where they did the preparation of bodies. When we took over, we did it for a couple years there, and then we decided we’d do all prep work in Wentzville.

P: Is there much difference between embalming back in the 1920s, 30s, 40s and what you do now?

JP: Not really, but the chemicals have gotten a lot more sophisticated. The chemicals were delivered from STL.

P: I guess you’ve used Paul Kamphoefner a lot for gravedigging.

JP: Paul has dug many a grave for us. He’s very good and he’s dug almost all the graves in the area – Augusta, Femme Osage, New Melle…all around. He’s still doing it and his son is helping him.

P: Let’s talk about your furniture store.

JP: The furniture store came about when we bought out the Neiburg funeral business in Wright City. They had a furniture store and that’s how we got into the furniture business. And we kept that running for…I don’t remember exactly how many years…not that many, because it became a real burden to run a furniture store and a funeral business at the same time.

P: I think you told me once there’s a historical connection between furniture and undertakers.

JP: The furniture business came about because they’d make caskets along with furniture.

Dearly beloved, according to Funerals 360.com: The modern casket industry that exists in the U.S. today began to take shape in the early 1800s, when local furniture and cabinet makers also served as undertakers (and vice versa). There was no mass production of caskets at the time--they were made by hand as needed.

Also worth mentioning, poet Thomas Lynch, in his 1997 book, The Undertaking (a National Book Award Finalist), tells us some embalming history he learned from his father who was also a funeral director. Lynch wrote, “…embalming got to be, forgive me, de rigueur during the Civil War when, for the first time in our history, lots of people – were dying far from home and the families that grieved them. Dismal traders worked in tents on the edge of the battlefields charging, one reckons, what the traffic would bear to disinfect, preserve, and “restore” dead bodies – which is to say they closed mouths, sutured bullet holes, stitched limbs or parts of limbs back on, and sent the dead back home…”

P: It’s interesting that you would own a funeral home in such a small and remote town as Augusta. Does this work much to your benefit, or do you feel sometimes you’re doing it just to help out our end of the county?

JP: That’s exactly right. Right now, we’re keeping it just to help the people in that area have a place to hold their services.

P: Well, thank you. Tell me about your Augusta employees. I know Earl Mallinckrodt worked there, and Jan also.

JP: Earl helped us for several years, and when we got a call over there, we’d pick up the body, prepare it in Wentzville, lay it out in Augusta, and Earl would work the visitation and help us with the funeral. Olie Thilking helped us before Earl.

P: I’m thinking now about the transportation of bodies. What did your father, Tarlton, use…wagons?

JP: Yes, my dad started out with a horse-drawn hearse. Then, naturally, they went into motorized vehicles, and then they started using motorized hearses for ambulances. His ambulance business ran until SCC decided to have their own ambulance service. That’s when we got out.

P: Did your dad have many employees…to do an ambulance business on top of...

JP: Yes, they worked for us when we had the Mercantile Store…and when we got a call…we’d take one or two from the Mercantile and use them on the ambulance…and they also helped with the funerals.

Gentle mourners, in my blacksmith story, we learned that Olie Thilking had a station wagon to do his pall bearer stuff, as Paul Hopen called it.

Fred Dressel was kind enough to send me a link which depicts what he remembers as the model and color of said vehicle. Fred texted: “Since it had a single blue beacon light on top, as kids we all thought it was the town ambulance. I don’t know if that’s the case or not. Later we thought it was ironic that Olie was an ambulance driver and also an owner of Pitman-Thilking Funeral Home! That certainly was a funny quirk about growing up in Augusta.” What the kids didn’t know back then was that there was no quirk at all because funeral homes and ambulances went hand in glove back in the day.

I have included an internet photo of a 1969 gold Chevy wagon. Does this car look familiar to anyone? Can you picture a blue light on top? It’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood; can you say dies irae?

BTW what’s up with the S-shaped scrolls on hearses? https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/66084/why-do-hearses-have-s-shaped-scrolls-where-back-windows-should-be

And while I have paused the interview, I want to tell my readers about the fatal poisoning of Tony Hepperman on March 3, 1940. Here’s a link to a lengthy summary of the sordid event: https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/3551228/state-v-hepperman/ But allow me to give you my abridged version. There once was a woman named Emma who was married 7 times, and she poisoned 5 of those spouses. Her last victim, Tony Hepperman, was a farmer from Wentzville, and this is where Tarlton Pitman enters the story.

P: While I was doing a little research on your dad, Tarlton, I came across the 1940 Hepperman murder trial…which must have been a big deal.

JP: Yes, it was. But the thing that was so bad about it was that they came to our store, and they bought the poison there…and they used it on Mr. Hepperman. Now…they (the highway patrol) came and got my dad…she had gone in to STL, and they weren’t sure exactly what she looked like…but they knew that my dad knew because we were selling her that stuff (arsenic) in the store, not knowing what she was using it for.

He went with them to STL, and when they got there, they set up a lookout point and waited for her to come by…and they got her.

P: And your family knew the victim, Tony?

JP: Yes, my dad knew a lot of the farmers around. (Tarlton’s business buried Anthony Hepperman.)

P: Have you done interments in private cemeteries…like on a farm?

JP: Oh yes, and there are several places here in SCC that my dad and myself…we’ve done burials…on private farms. Now when they do that, they have to get special permission through the county court to use that private property as a cemetery.

P: The Matson family in Matson had their own large cemetery. Have you worked there?

JP: If I remember right, I think I had one burial there…years ago.

P: I think you just set a record for my fastest interview. Thanks for your concise answers.

JP: I truly enjoyed talking with you and telling you some of the stories that went on in our business.

P: Hey, do you know any good undertaker jokes?

JP: (Chuckle.)

Gentle readers, we can just end on that light note…but I’m gonna bring you right back down…with a recording of my rendition of a classic sad funeral song, St. James Infirmary Blues. As always, I have some cool photos for you too.

Looks like there’s going to be a part 2 and probably a part 3 to my funereal tome. We’ll be taking a closer look at the bank building, resurrect Olie Thilking, and I’ll share a chat with the farmer, gravedigger, and (in my mind) man-of-steel, Paul Kamphoefner. There’s still an interview with Eric Pitman, and another interview regarding an at-home wake that took place in 1997 in the Augusta area. Also, to come: some funeral writing from Ida Gerdiman which Nancy Overstreet has brought to light.

Be good, and if you can’t be good, be curious.

Paul

Comments